Cortlandt Forum has a nice short article on Nocturnal leg cramps:

By Russel Kirkby, MD, and Brian Alper, MD, MSPH

Description• Involuntary nighttime painful leg muscle contraction that does not relax

ICD-9 codes• 728.85 spasm of muscle • 729.82 cramp of limb

Prevalence• 95% of people sometime in their lives • Especially common in women and elderly

Most commonly affected muscle groups• Calf • Foot

Etiology• Most commonly no cause found• Possible causes (or associated conditions) include —Fluid and electrolyte imbalance: hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, chronic diarrhea, hemodialysis —Endocrine disease: thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, Addison’s disease — Neuromuscular disease: nerve-root compression, motor-neuron disease, mononeuropathies, polyneuropathies, dystonias —Drugs: calcium channel blockers (nifedipine), diuretics, phenothiazines, fibrates, selective estro- gen receptor modulators (raloxifene), ethanol, morphine withdrawal —Toxins: lead, strychnine, spider bites —Congenital disease: McArdle’s disease, glycogen storage disease, autosomal dominant cramping disease —Peripheral vascular disease —Iron deficiency anemia —Liver cirrhosis, chronic alcoholism, sarcoidosis —HIV myelopathy• Pathophysiology speculative, may include reduced blood flow and oxygen supply

Likely precipitating factors• Activity excessive for condition of muscle• Sleeping prone or supine with toes fully extended • Pregnancy (insufficient calcium intake)• Older age

Complications• Insomnia • Irritability • Anxiety • Depression

Clinical evaluation• History of onset and clues to underlying condition• Drug history crucial• Local exam: arterial pulses, skin, nerves—Pulses and capillary fill (rule out vascular compromise) —Assess skin changes—Sensation/vibration

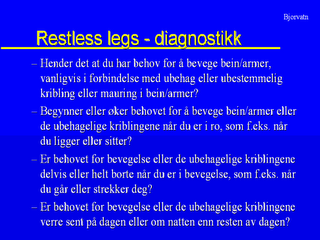

Differential diagnoses• Intermittent claudication• Peripheral neuritis• Restless legs syndrome• HIV myelopathy• Physiologic cramps due to heat, exercise, excessive activity• Electrolyte abnormalities: hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia• Polycythemia• Endocrine disease: diabetes, thyroid disease, parathyroid disease, adrenal disease • Muscle diseases: glycogen storage or mitochondrial

Testing (for recurrences or underlying disease)• Electrolytes • Glucose • Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine • Calcium, magnesium, phosphate • Hemoglobin, ferritin • Zinc • Liver function tests • Thyroid function tests• HIV if appropriate• Doppler studies of arteries• Electromyelography

Nonpharmacologic management• Reassurance to exclude causes that might cause patients concern, e.g., vascular disease• Major thrust is to avoid sleep disturbance• Trial of omitting possible causative medication• Other treatments to consider—Local heat —Massage —Osteopathic manipulative therapy (OMT): myofascial release, facilitated positional release

Medications to consider• Quinine sulfate 200-400 mg nightly —Beware long-term use.—Rare but serious side effects described (disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, hemolytic uremic syndrome) —Consider monitoring complete blood count or platelets.• Other drugs similar to quinine —Hydroquinine 300 mg —Quinidine sulfate 400 mg• Other drugs not similar to quinine—Verapamil 120 mg nightly—Gabapentin (Neurontin) may reduce frequency and severity of muscle cramps.—Magnesium not clearly effective• Benzodiazepines (clonazepam, diazepam) or baclofen—Not traditionally associated with nocturnal cramp therapy but helpful in other spastic muscle conditions, e.g., tetanus, status epilepticus, and back muscle spasm —Address treatment goals of avoiding sleep disturbance.• Gastrocnemius trigger point injection of 1% lidocaine• Randomized n-of-1 trials alternating drug and placebo may determine efficacy of specific drugs for individual patients.

Prevention• Stretching exercises — e.g., nightly or twice daily • 20-minute walk may enhance stretching exercises.

See for www.dynamicmedical.com) references.

Quinine is the most commonly used treatment for this poorly understood condition; however with this medication cinchonism needs to be monitored for.